Waking up in an emergency room with my hands strapped to the bed, with a tube down my throat and into my stomach, I felt like I was going to explode. I didn’t know where I was, and I barely remembered what I had done. I managed to choke up the tube only to have it violently shoved down into my stomach, where they poured five gallons of fluid into my stomach that was incapable of holding that much fluid, and I vomited and soiled myself uncontrollably. It was the most horrific and humiliating feeling. I felt embarrassed and humiliated by my own body. I felt myself disappear, watching myself from the ceiling, horrified by what I was witnessing.

Once it was over, an officer came to my room and informed me that I was being put on a 51/50, which is a three-day legal hold. Being that I only had county insurance at the time, I was sent to a county hospital. This wasn’t my first suicide attempt. I have made nine suicide attempts throughout my adulthood, beginning when I was 17 years old, but none of them were as severe as that time when I was 19 years old. The rest of my suicide attempts would be considered a “cry for help.”

When I first noticed that my mental health was declining was when I was 14 years old. My behavior became horrific. I was lying to anyone and everyone about the only thing I thought that mattered to people ─ abuse. When I first started acting out at 14, my dad took me for a car ride and told me, “You don’t know the meaning of pain like your mother does.” He continued, “Your mother was ritually abused, forced to eat a baby’s flesh, and drink their blood.” This was more information than a 14-year-old girl needed to know, but it made it loud and clear what real pain consisted of.

“My pain wasn’t real,” I thought. “It didn’t matter. It wasn’t important,” I would tell myself. Not according to my dad. However, I knew I was hurting. I knew something was wrong. I have knots in my stomach daily. My heart raced like a jet plane with anxiety; I didn’t want to die for no reason. Kids at school knew I was different. They knew something was wrong with me. For one thing, I was a lesbian. I discovered my attraction to other girls when I was 13 through a sexual encounter I had with a “friend.” I kept it a secret, coming from a Christian family, and I strove to be normal by getting a boyfriend. But that attempt failed miserably when I couldn’t kiss him, and he figured it out on his own that I wasn’t attracted to boys.

Word got out, and I think that was part of the reason I was bullied so badly. It was the ‘90s, and I was from a small town that didn’t think highly of gays or lesbians. However, kids sensed something different about me, aside from being a lesbian. I walked through the halls, staring at the ground; I rarely talked in class, and I had no friends besides my best friend, who was 400 pounds, and kids called a “beached whale.”

She had a few friends, one boy who was gay, but I hid behind her and stayed quiet. To the other kids, we were considered the “loser crowd.” My best friend was the only one that I talked to, and she was aware of the darkness within me because, although she hid it from the world, I knew she felt that same darkness. She was the first one to introduce me to alcohol. Her mother allowed her to drink if she didn’t leave the house. I spent the night at her house almost every weekend, and the same rules applied to me. We got drunk every Friday night. My parents were in the dark about my secret, just like they were in the dark about my sexuality. I was like a stranger living under their roof.

My friend was considered a loser like me, as if I attracted losers like a magnet. Teenagers didn’t care whether someone was depressed, hurt, or felt alone. They saw that as a reason to bully someone. That was me. I was spit on in the halls, tripped and purposefully bumped into, and called names like “loser” or “freak.” I knew that they were right. I knew something was deeply wrong with me. I was slipping more and more into darkness.

My friend was the glue that held me together. My parents moved me to a private school that consisted of 6th through 12th graders, yet it only had 60 students in total. They thought it would be the answer to the bullying at the public school. It was not. Apparently, private Christian students saw kids from public schools as outcasts and sinners. So, I was avoided at all costs. I still had my best friend, and we still had our weekend sleepovers, which consisted of drinking and raw, honest conversations. It was the only time I felt free to talk about my pain. “I don’t know what is wrong with me,” I told her.

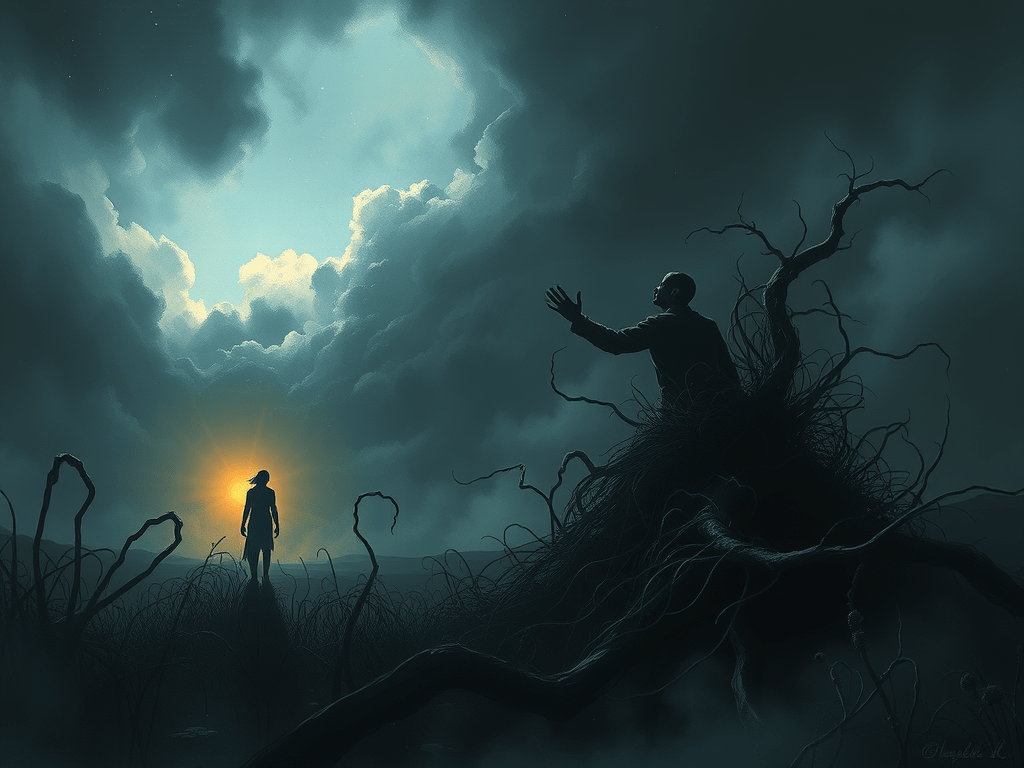

“The same thing that is wrong with me…our lives suck,” she answered. By the end of my sophomore year, my friend moved away, and that shattered my heart like a shattered mirror. She was no longer the glue that held me together. My junior year, since moving me to a Christian school was obviously not working, my parents resorted to home-schooling me, which was basically independent study because I did my schoolwork on my own. By then, I was 16 and my life was falling apart. I had sunk into darkness like I had dropped into a 40-foot well with no hope of being rescued.

By this time, I was begging my parents to get me some help. I knew deep down that there was something wrong with me. My dad just said, “You know you are afraid of needles, and a hospital will stick you with a needle every day. This is just a phase. It’s called being a teenager. You don’t need any help.” It was true. I absolutely hated needles, but I was willing to endure anything to get some help. I was sinking further and further into a pit and felt like I was being buried alive. I was suffocating in despair. I told my mom and dad on multiple occasions that I wanted to die, and yet again, they responded that it was just a phase.

By the time I was 17, I had had it with life. I was going to prove to my family that there was something severely wrong with me. So, one night, when my mom was having a bible study at our house, I went to my room and swallowed a bottle of over-the-counter sleeping pills called Unisom, not knowing that it would not kill me. Suddenly, I panicked. I was from a Christian family and was taught that suicide would send you to hell. I had been having nightmares of hell since I first learned I was a lesbian, but I had hope that I could change. However, I couldn’t reverse a suicide attempt, and I didn’t want to go to hell.

I went downstairs and asked to talk privately with the only woman there whom I trusted. I had her come to my room and told her what I had done. She went downstairs and told my mom what I did, which the whole group heard, and I listened to my mom crying as she called 911, and all the other women comforting her. Not one of them came upstairs to see how I was doing, not even my mother. I felt isolated, thrown out to sea. One of the ladies told me that an ambulance was on its way, and I waited out on the porch. When the police arrived, I felt like a criminal, but I was relieved I wasn’t put in handcuffs. “Where are your parents?” they asked. “My mom is in the house with her friends,” I answered, “my dad is not home. My mom won’t come out.” The officers looked at each other. “No wonder the kid is screwed up,” one of them said, “the ambulance is here, come with us.”

“We will take from here, officers,” the paramedic said. “I take it the parents aren’t home?” she asked. The mother is, but she won’t come out. The paramedic shook her head. “Okay, darling, hop in and lie on the gurney. “What did you take?” she asked.

“A bottle of Unisom sleeping,” I replied.

“You will be happy to know that won’t kill you. You are going to be given charcoal, and once you are cleared in the ER, you are going to be evaluated at a children’s psychiatric facility because you are not 18, so you can’t be admitted to an adult facility. I was relieved that I wasn’t going to die and that I was finally going to get some help.

Now, this personal essay is not a life story. I am writing a memoir about all of this in more detail, but that first suicide attempt became a downward spiral into my mental illness. I was diagnosed with bipolar II disorder, which was later changed to bipolar disorder with psychotic features. I moved from place to place, never truly finding where I belonged. I rented rooms that never lasted, I moved in with friends, but my problems were always too much for them, and when my parents decided I needed a case worker, I was forced into group homes, none of which were pleasant places to live, but at least it was a roof over my head.

When I was 19, I made that serious suicide attempt in which my stomach was pumped, and I spent four days in the ICU—the attempt I described at the beginning of this essay. That is when someone went to bat for me, and to this day, I don’t know who, but they applied for disability for me, and I was approved. That was how I got into those group homes.

However, since then, I managed to leave the group homes and rent a room from a friend, which was the beginning of my life turning around. I did end up in a psychiatric hospital a few times over the seven years I lived there, but they became far and few between. I started college and was making perfect grades until I was invited to join an honor society. I had never been good at anything in my life, and I was finally giving my family something to be proud of. After seven years of living there, my friend got Dementia and had to go live with her youngest son, leaving me unable to pay the whole rent.

So, I moved in with my parents, who had a different opinion of me by now than they did when I was younger, and I continued to go to college and continued to make perfect grades. However, in all honesty, college wasn’t really my dream. I was doing it for the pride of my parents, especially my dad. My dream in life has always been to become a writer, so I made the hard decision to quit school and pursue writing. I am about to publish my first book, which is a seven-week devotional for the LGBTQIA community. It’s my dream to bring hope and love to the community and show them that God has unconditional love for them, regardless of who they are.

I will write another personal essay specifically about my journey to reconcile my faith with my identity. This essay focuses on living with mental illness. I have talked about my many hospitalizations and the instability of my living arrangements. Still, I have not talked about what it is like living with bipolar disorder with psychotic features. My life has been a roller coaster ride with high highs and low lows, and everything in between. I experienced brief episodes of mania, which I now have learned was really hypomania because I didn’t have the “on top of the world” feeling that mania presents. I had extreme bouts of irritability and anger. I have had suffocating depression and anxiety, which could last weeks or months. Along with the extreme mood swings, I was seeing shadows when none were there, hearing noise in my head that sounds like a crowded room of people talking, and having much suicidal ideality.

I have lived with these symptoms since I was 13 years old, increasing to a severe level when I was 16, only getting officially diagnosed when I was 17. Sometimes in my life, those symptoms were easier than others. It was during periods of intense stress that my symptoms magnified. When my life was relatively calm, the symptoms subsided. As I said before, I have made nine suicide attempts in my life, and I am unable to recall when or where I was at the time. I have been hospitalized more than 50 times in my life for suicidal ideation. To say I have gone through many dark places in my life is an understatement. I have only begun to stabilize mentally, with the proper medication, in the last several years.

To say I am completely healed or recovered from my mental illness would be a lie. I still have dark times, I still struggle with anxiety, I still sometimes see shadows or hear noise in my head. What is different now, though, is that I have learned coping skills to deal with these symptoms. I write journals, do artwork, take bubble baths, use scented lotions, do meditations, talk about my thoughts and feelings, listen to calming or uplifting music, watch TV shows or movies that bring me joy, and write.

When I remember and commit to doing these things, the symptoms I still have are manageable. They don’t cripple me anymore. They don’t destroy me anymore. At times, I have days that I feel like I am suffocating in despair again, and in those times, my therapist tells me she is holding my hope until I can keep it for myself. Knowing she has my hope gives me something to hold onto when I feel like I am hanging on by a thread. It is a life jacket that she throws out to me in the dark sea. Then, not long after, I put that life jacket on and started to swim to the boat, where she was waiting for me with open arms.

Life with bipolar disorder with psychotic features is considered a permanent illness in Social Security’s eyes. I agree with that because I am entirely dependent upon my medication to keep me stable, and the medication only does so much. For the symptoms that persist, I must rely heavily on my coping skills. The coping skills that work best for me are journaling honestly, meditation, taking baths, talking through my feelings with my therapist, and watching shows that bring me joy and are a good distraction. I may always struggle with symptoms, but they no longer bring me to hospitalization or a feeling of lack of hope. When the symptoms present themselves, I now have the tools I need to deal with them, even if it means my therapist holds my hope for me. She has been my lifesaver and hopes for continued healing.

Leave a comment